It always interests me how people react when I tell them that I have a business that teaches people how to create a family archive. A while ago I was working in the stacks with an archivist who was visiting to look at some of the materials in our collection. When I told him about my business his immediate thought was that people would want to give their things away and donate them to an archive. He’s usually at the receiving end of that equation and I could see he was concerned that people would throw things away before they made it to an archive where the archivist could preen over it, and it could be preserved into perpetuity.

I explained that teaching people how to dispose of their materials wasn’t my main intention. My focus is to teach them how to keep and preserve their items.

But, when I thought about it, I saw he was right. Many people don’t want to keep everything, yet they don’t know what to do with it. You may also feel that your house is not the best place for some of the precious historical items that have been handed down  to you. This is exactly the reason many people donate materials to a trusted archive that is better equipped to ensure the article’s long-term survival.

to you. This is exactly the reason many people donate materials to a trusted archive that is better equipped to ensure the article’s long-term survival.

If you don’t want to keep everything, or

think you have something of significant historical value, the best thing to do is to contact your local historical society.

I suggest you call the place that you are most familiar with, or the one that is closest to you. If they don’t want your items, they may be able to tell you who will. Make sure the archive you contact is a bona fide repository with real archivists working there. In my area there are small town historical societies that are run by interested volunteers who might not know any more about what to do with the materials than you do. The Staff section of the archives’ website should let you know if there is a qualified person on staff.

Most archives also list on their websites a Mission Statement, and maybe even a Collection Policy. Look under the About section for this information.

The Mission Statement or the Collection Policy will give you an idea of whether or not that archive collects the type of materials you have.

If you own a 19th century doll collection, you might want to give it to an archive that specializes in 19th century dolls. It doesn’t have to go to a place that is that specific, but housing your materials in a place with other like materials will raise the chances that it will be seen by patrons. If you are unsure about where the best place for your materials would be, or don’t want to do the research, make the initial phone call to the archivist. They will set you on the right track. They may know off the top of their heads where they best place for your materials will be.

If you own a 19th century doll collection, you might want to give it to an archive that specializes in 19th century dolls. It doesn’t have to go to a place that is that specific, but housing your materials in a place with other like materials will raise the chances that it will be seen by patrons. If you are unsure about where the best place for your materials would be, or don’t want to do the research, make the initial phone call to the archivist. They will set you on the right track. They may know off the top of their heads where they best place for your materials will be.

The next question is should you give it away or should you sell it to the archive?

You could give it away. Many people do. Matter-of-fact, most people do. It depends what it is. If you have an expensive silver tea set that was your great-grandmothers and you have no one to leave it to, and you think a local archive might be interested in it, by all means have it priced by a reputable dealer then approach the archive. Archives will absolutely pay for something if it is of value. But if it something of less value, or very little value on the open market, consider donating it. Archives tend to work on very limited budgets and often they won’t take something unless it’s donated.

Before starting to create a family archive consider who you are creating the archive for. If you are not one of those lucky people who have photographs and letters from a long, lost relative who lived during the Civil War or the American Revolution, it’s probably not on your radar to think very far ahead when considering who you are creating this archive for. You may think of creating it for yourself in the event of a disaster. You may think of creating it for your siblings and cousins who you will share with at the next family gathering. Most people think of their children and grandchildren when they think of preserving their documents. Typically this is as far ahead as most people think.

Before starting to create a family archive consider who you are creating the archive for. If you are not one of those lucky people who have photographs and letters from a long, lost relative who lived during the Civil War or the American Revolution, it’s probably not on your radar to think very far ahead when considering who you are creating this archive for. You may think of creating it for yourself in the event of a disaster. You may think of creating it for your siblings and cousins who you will share with at the next family gathering. Most people think of their children and grandchildren when they think of preserving their documents. Typically this is as far ahead as most people think. has known you directly has died. Think of your forebear who would think it was cool to have memorabilia from the 20th and 21st centuries. Why do I want you to expand your thinking about who you are leaving your archives to? Because you will tell your story in a very different way; you will describe a letter, a deed, a photograph, a quilt differently. Instead of indicating that a picture is of, “Aunt Mary and her friend, Lou,” you would write instead, “Mary Louise Smith and Lou Johnson. They were a couple for many years, but never married.” If you write for your children you will assume they know who “Aunt Mary” is and that they know that Lou was the boyfriend she never married. The person who is born after the last person who has known you has died, will not know that.

has known you directly has died. Think of your forebear who would think it was cool to have memorabilia from the 20th and 21st centuries. Why do I want you to expand your thinking about who you are leaving your archives to? Because you will tell your story in a very different way; you will describe a letter, a deed, a photograph, a quilt differently. Instead of indicating that a picture is of, “Aunt Mary and her friend, Lou,” you would write instead, “Mary Louise Smith and Lou Johnson. They were a couple for many years, but never married.” If you write for your children you will assume they know who “Aunt Mary” is and that they know that Lou was the boyfriend she never married. The person who is born after the last person who has known you has died, will not know that. episode people are deeply touched and moved when they learn that a great-great-great-grand-parent who they never knew, lived through a major historical event or disturbing personal tragedy. Whether the history tells of a celebrated past, or a painful circumstance, we are connected to our past. We care deeply about our forebears lives. We often can detect how what happened to them shaped who we are today. Stories and legends get passed down for generations, some true, some only partially true. Today, we have the opportunity to tell the story of our ancestors and to add our story to the mix.

episode people are deeply touched and moved when they learn that a great-great-great-grand-parent who they never knew, lived through a major historical event or disturbing personal tragedy. Whether the history tells of a celebrated past, or a painful circumstance, we are connected to our past. We care deeply about our forebears lives. We often can detect how what happened to them shaped who we are today. Stories and legends get passed down for generations, some true, some only partially true. Today, we have the opportunity to tell the story of our ancestors and to add our story to the mix.

When my childless Aunt Hope died I took a box of photographs stored in her closet that my cousin was going to throw them out. I couldn’t wait to get home to see what was in them. I opened the box anxiously anticipating what I would find hoping to see pictures of my father and aunts and uncles when they were little.

When my childless Aunt Hope died I took a box of photographs stored in her closet that my cousin was going to throw them out. I couldn’t wait to get home to see what was in them. I opened the box anxiously anticipating what I would find hoping to see pictures of my father and aunts and uncles when they were little.

A true bibliophile is like that.

A true bibliophile is like that. Along the road of life I’ve met two women who gave up their libraries. One of them I met a month after she had taken the drastic step as she moved across the country to attend grad school. Why get rid of your books, I asked? Why not just put them in storage? I watched both women go through a grieving process as they spoke lovingly of one of their favorite books only to realize they were no longer the owner of said book. It was painful. I have no plans to get rid of my books. My sister always talks about purging and downscaling. I understand that perspective, but acknowledge that as long as I’m here on this green earth, there are certain things I want near me, and my books are pretty high up on the list (along with lots of favorite clothes).

Along the road of life I’ve met two women who gave up their libraries. One of them I met a month after she had taken the drastic step as she moved across the country to attend grad school. Why get rid of your books, I asked? Why not just put them in storage? I watched both women go through a grieving process as they spoke lovingly of one of their favorite books only to realize they were no longer the owner of said book. It was painful. I have no plans to get rid of my books. My sister always talks about purging and downscaling. I understand that perspective, but acknowledge that as long as I’m here on this green earth, there are certain things I want near me, and my books are pretty high up on the list (along with lots of favorite clothes). Considering the great love affair we have with our books, the question remains, what do we do with them after we have passed. If you make no provisions, your children will probably take what they want, invite others in the family to take what they want, then give the rest to Salvation Army. Instead, you could will your books to a local library. Depending on what’s in your collection, you could consider donating them to a university, perhaps your alma mater, a college or a local public library. Of course if you think your children might be interested in the collection, you could stipulate that whatever they don’t want will go to the library. You could also select different libraries for different parts of your collection – the history books, science books, and computer books to go to a college library while the trashy novels you love could go to a public library.

Considering the great love affair we have with our books, the question remains, what do we do with them after we have passed. If you make no provisions, your children will probably take what they want, invite others in the family to take what they want, then give the rest to Salvation Army. Instead, you could will your books to a local library. Depending on what’s in your collection, you could consider donating them to a university, perhaps your alma mater, a college or a local public library. Of course if you think your children might be interested in the collection, you could stipulate that whatever they don’t want will go to the library. You could also select different libraries for different parts of your collection – the history books, science books, and computer books to go to a college library while the trashy novels you love could go to a public library. What will happen when they get to the library? The Acquisitions Librarian will go through the books to determine if there is something that will fit within the scope of their collection policy. All libraries have a collection policy that stipulates what types of books they will collect and what kinds they will not. If there are books in the collection that the library doesn’t want, but they know of another library that collects that kind of material, they will pass it on to the appropriate library. The remainder of the collection may be sold cheaply to their patrons, they might be sold to a used book store, or they may be sent overseas to fill the libraries of third world countries in desperate need of good books. In one way or another, the books that have brought so much joy to our lives, will hopefully find their way into the hands of a new caretaker who will value them as much as we have.

What will happen when they get to the library? The Acquisitions Librarian will go through the books to determine if there is something that will fit within the scope of their collection policy. All libraries have a collection policy that stipulates what types of books they will collect and what kinds they will not. If there are books in the collection that the library doesn’t want, but they know of another library that collects that kind of material, they will pass it on to the appropriate library. The remainder of the collection may be sold cheaply to their patrons, they might be sold to a used book store, or they may be sent overseas to fill the libraries of third world countries in desperate need of good books. In one way or another, the books that have brought so much joy to our lives, will hopefully find their way into the hands of a new caretaker who will value them as much as we have.

Providence Sunday Magazine about the Providence Public Library. I thought, “How cool would it be to walk into that building everyday to go to work?” When I finally took the leap and went to grad school, I decided to become an archivist instead. I love working with older documents. One of the things I loved when I was new in this field and doing my internships is that when I stumbled upon a cool original document while processing collections, I would immediately tell my supervisors, people who have been working in the field for twenty years or more.

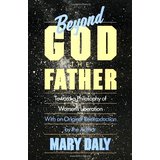

Providence Sunday Magazine about the Providence Public Library. I thought, “How cool would it be to walk into that building everyday to go to work?” When I finally took the leap and went to grad school, I decided to become an archivist instead. I love working with older documents. One of the things I loved when I was new in this field and doing my internships is that when I stumbled upon a cool original document while processing collections, I would immediately tell my supervisors, people who have been working in the field for twenty years or more. internship at the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, I had the honor of doing an initial survey on the papers of Mary Daly. In her collection I found letters from Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, and Angela Davis, among others. When I told my supervisor, Maida, she got excited and said, “Let me see.” I thought she would have seen it all by then, having worked in Smith’s archive for over twenty years, but she was impressed and curious and had to see. The women’s whose documents I found might not mean much to you, but I grew up listening to them, reading their words, and learning from them. They’re like rock stars in my world.

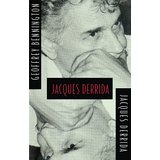

internship at the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, I had the honor of doing an initial survey on the papers of Mary Daly. In her collection I found letters from Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, and Angela Davis, among others. When I told my supervisor, Maida, she got excited and said, “Let me see.” I thought she would have seen it all by then, having worked in Smith’s archive for over twenty years, but she was impressed and curious and had to see. The women’s whose documents I found might not mean much to you, but I grew up listening to them, reading their words, and learning from them. They’re like rock stars in my world. my students found a signed letter by Jacques Derrida, the postmodern philosopher. You would have thought he had won the lottery he was so excited. He had read a number of Derrida’s books and considered him a hero. A few days later when I was surveying another collection, I stumbled upon handwritten thank-you notes

my students found a signed letter by Jacques Derrida, the postmodern philosopher. You would have thought he had won the lottery he was so excited. He had read a number of Derrida’s books and considered him a hero. A few days later when I was surveying another collection, I stumbled upon handwritten thank-you notes  from Erica Jong, author of Fear of Flying, and Hillary Rodham Clinton. That’s what I love about working in the archives. We get to see and feel the documents of people we love and admire, and more importantly, preserve them so a researcher in the future can experience the same thrill of discovery.

from Erica Jong, author of Fear of Flying, and Hillary Rodham Clinton. That’s what I love about working in the archives. We get to see and feel the documents of people we love and admire, and more importantly, preserve them so a researcher in the future can experience the same thrill of discovery.